Here are examples of everything new in ECMAScript 2016, 2017, and 2018

It’s hard to keep track of what’s new in JavaScript (ECMAScript). And it’s even harder to find useful code examples.

So in this article, I’ll cover all 18 features that are listed in the TC39’s finished proposals that were added in ES2016, ES2017, and ES2018 (final draft) and show them with useful examples.

This is a pretty long post but should be an easy read. Think of this as “Netflix binge reading.” By the end of this, I promise that you’ll have a ton of knowledge about all these features.

OK, let’s go over these one by one.

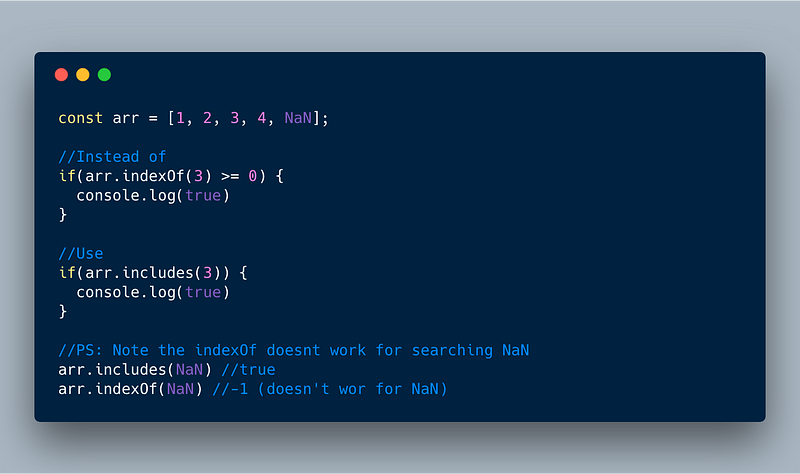

1\. Array.prototype.includes

includes is a simple instance method on the Array and helps to easily find if an item is in the Array (including NaN unlike indexOf).

ECMAScript 2016 or ES7 — Array.prototype.includes()

ECMAScript 2016 or ES7 — Array.prototype.includes()

Trivia: the JavaScript spec people wanted to name it

contains, but this was apparently already used by Mootools so they usedincludes.

2\. Exponentiation infix operator

Math operations like addition and subtraction have infix operators like + and - , respectively. Similar to them, the ** infix operator is commonly used for exponent operation. In ECMAScript 2016, the ** was introduced instead of Math.pow .

ECMAScript 2016 or ES7 — ** Exponent infix operator

ECMAScript 2016 or ES7 — ** Exponent infix operator

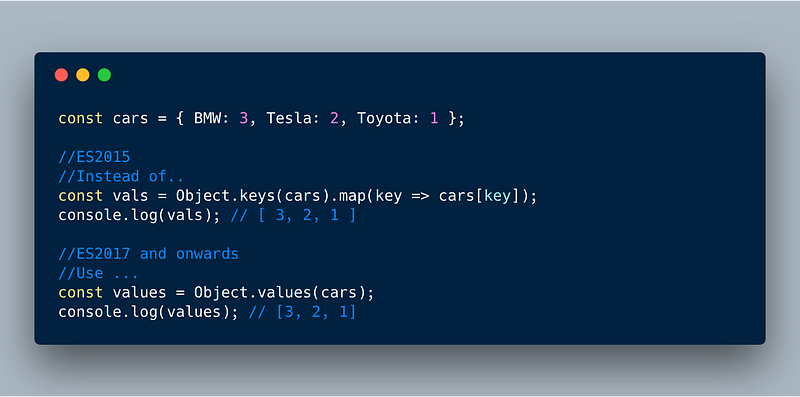

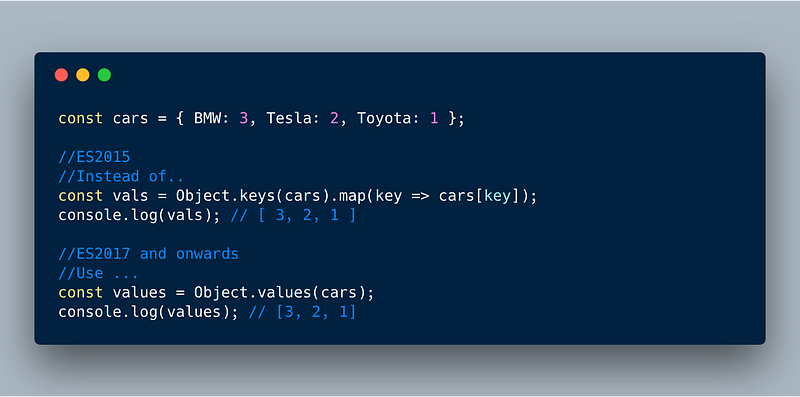

1. Object.values()

Object.values() is a new function that’s similar to Object.keys() but returns all the values of the Object’s own properties excluding any value(s) in the prototypical chain.

ECMAScript 2017 (ES8)— Object.values()

ECMAScript 2017 (ES8)— Object.values()

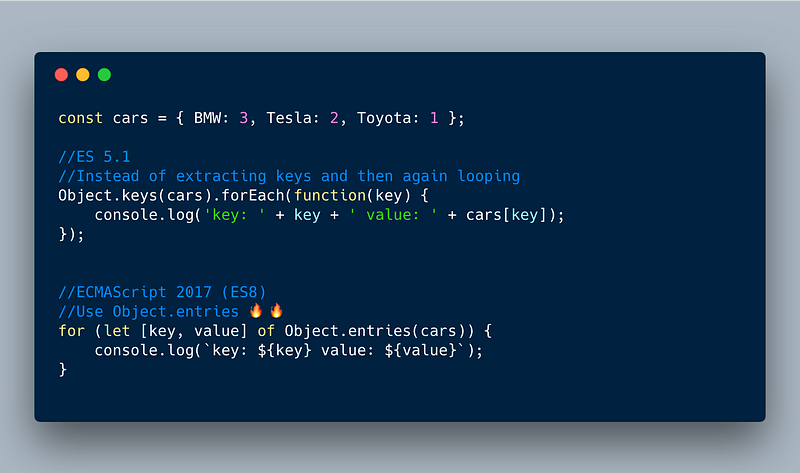

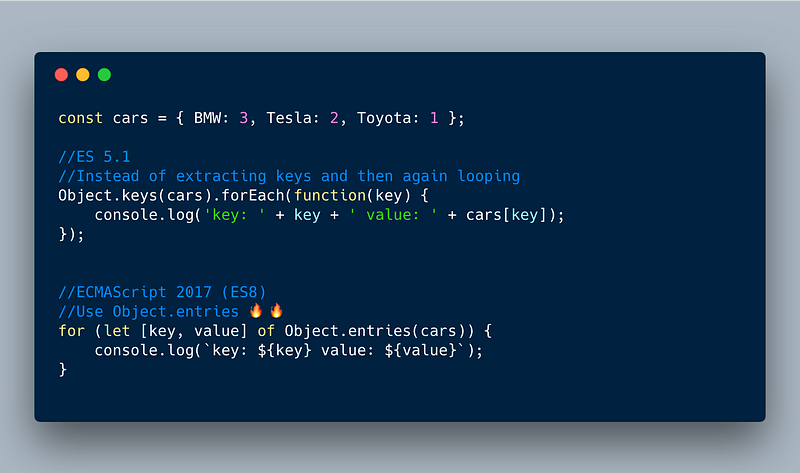

2. Object.entries()

Object.entries() is related to Object.keys , but instead of returning just keys, it returns both keys and values in the array fashion. This makes it very simple to do things like using objects in loops or converting objects into Maps.

Example 1:

ECMAScript 2017 (ES8) — Using Object.entries() in loops

ECMAScript 2017 (ES8) — Using Object.entries() in loops

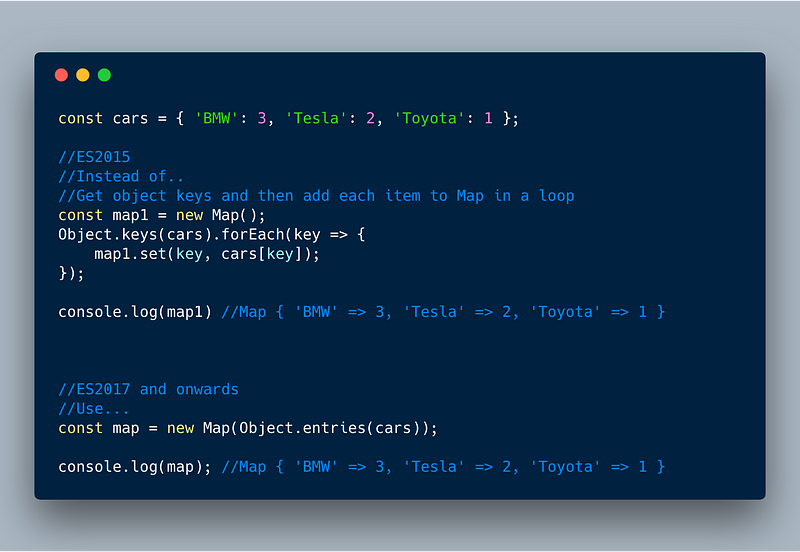

Example 2:

ECMAScript 2017 (ES8) — Using Object.entries() to convert Object to Map

ECMAScript 2017 (ES8) — Using Object.entries() to convert Object to Map

3. String padding

Two instance methods were added to String — String.prototype.padStart and String.prototype.padEnd — that allow appending/prepending either an empty string or some other string to the start or the end of the original string.

'someString'.padStart(numberOfCharcters [,stringForPadding]);

'5'.padStart(10) // ' 5' '5'.padStart(10, '=*') //'=*=*=*=*=5'

'5'.padEnd(10) // '5 ' '5'.padEnd(10, '=*') //'5=*=*=*=*='

This comes in handy when we want to align things in scenarios like pretty print display or terminal print.

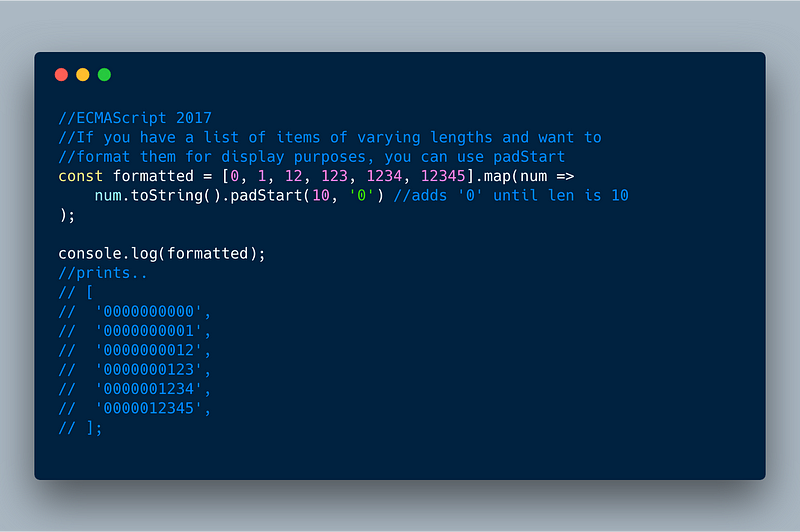

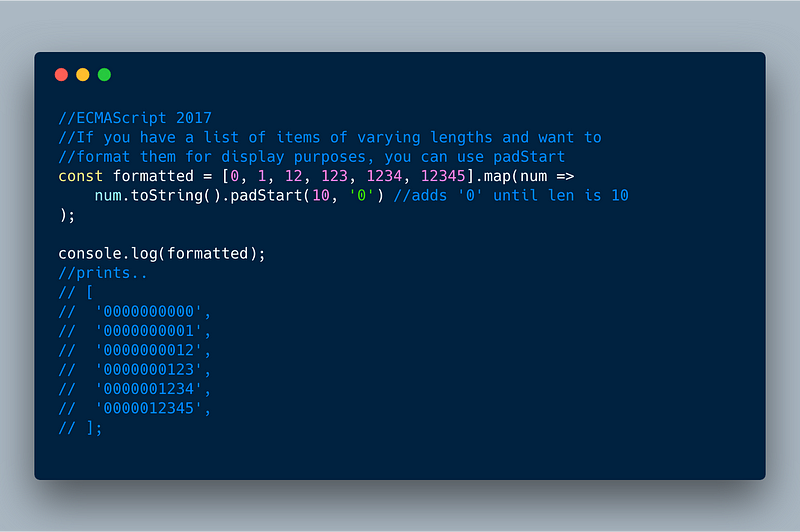

3.1 padStart example:

In the below example, we have a list of numbers of varying lengths. We want to prepend “0” so that all the items have the same length of 10 digits for display purposes. We can use padStart(10, '0') to easily achieve this.

ECMAScript 2017 — padStart example

ECMAScript 2017 — padStart example

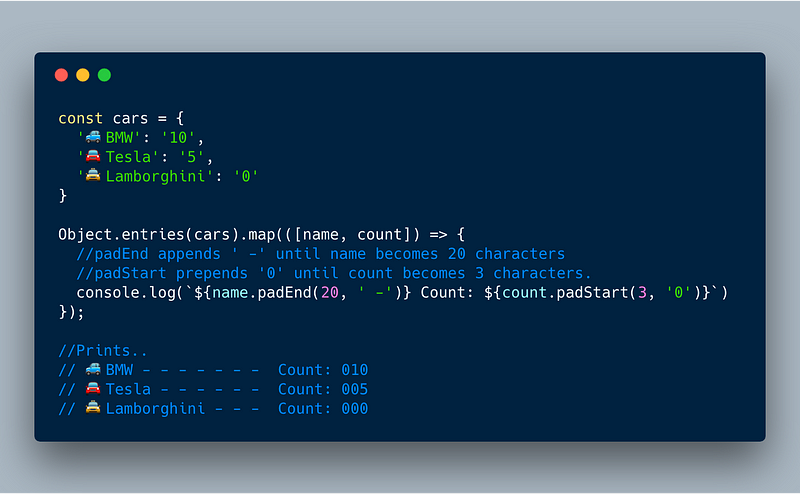

3.2 padEnd example:

padEnd really comes in handy when we are printing multiple items of varying lengths and want to right-align them properly.

The example below is a good realistic example of how padEnd , padStart , and Object.entries all come together to produce a beautiful output.

ECMAScript 2017 — padEnd, padStart and Object.Entries example

ECMAScript 2017 — padEnd, padStart and Object.Entries example

const cars = {

'🚙BMW': '10',

'🚘Tesla': '5',

'🚖Lamborghini': '0'

}

Object.entries(cars).map(([name, count]) => {

//padEnd appends ' -' until the name becomes 20 characters

//padStart prepends '0' until the count becomes 3 characters.

console.log(`${name.padEnd(20, ' -')} Count: ${count.padStart(3, '0')}`)

});

//Prints.. // 🚙BMW - - - - - - - Count: 010 // 🚘Tesla - - - - - - Count: 005 // 🚖Lamborghini - - - Count: 000

3.3 ⚠️ padStart and padEnd on Emojis and other double-byte chars

Emojis and other double-byte chars are represented using multiple bytes of unicode. So padStart and padEnd might not work as expected!⚠️

For example: Let’s say we are trying to pad the string heart to reach 10 characters with the ❤️ emoji. The result will look like below:

//Notice that instead of 5 hearts, there are only 2 hearts and 1 heart that looks odd! 'heart'.padStart(10, "❤️"); // prints.. '❤️❤️❤heart'

This is because ❤️ is 2 code points long ('\u2764\uFE0F' )! The word heart itself is 5 characters, so we only have a total of 5 chars left to pad. So what happens is that JS pads two hearts using '\u2764\uFE0F' and that produces ❤️❤️. For the last one it simply uses the first byte of the heart \u2764 which produces ❤

So we end up with: ❤️❤️❤heart

PS: You may use this link to check out unicode char conversions.

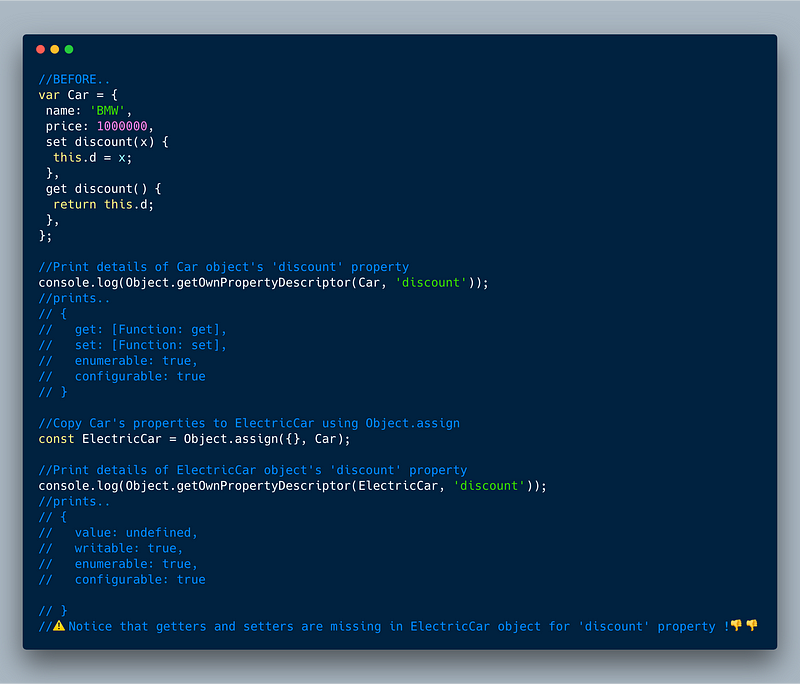

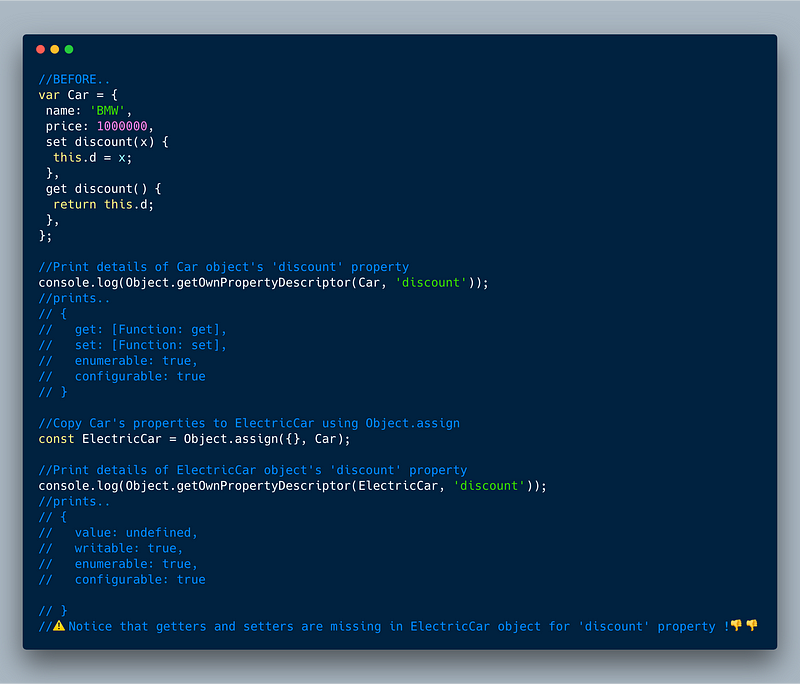

4. Object.getOwnPropertyDescriptors

This method returns all the details (including getter getand setter set methods) for all the properties of a given object. The main motivation to add this is to allow shallow copying / cloning an object into another objectthat also copies getter and setter functions as opposed to Object.assign .

Object.assign shallow copies all the details except getter and setter functions of the original source object.

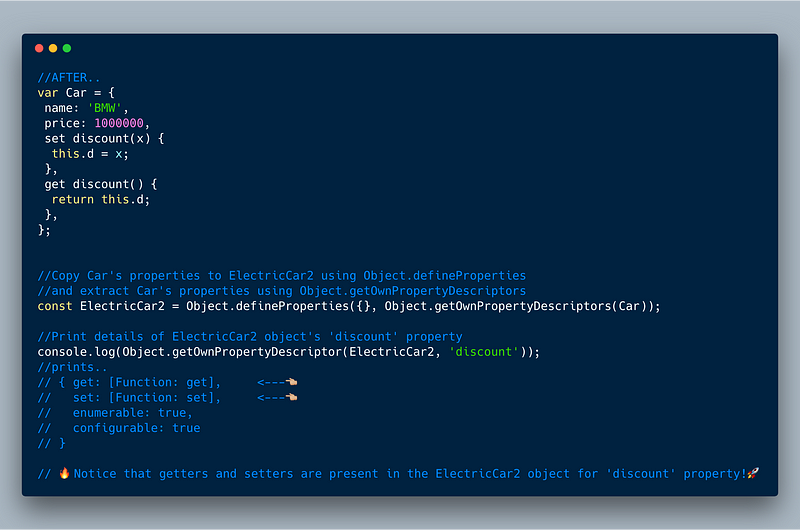

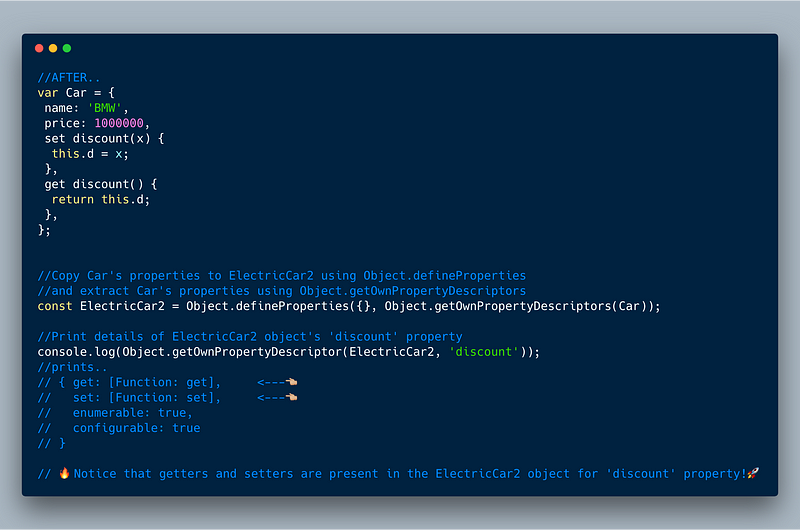

The example below shows the difference between Object.assign and Object.getOwnPropertyDescriptors along with Object.defineProperties to copy an original object Car into a new object ElectricCar . You’ll see that by using Object.getOwnPropertyDescriptors ,discount getter and setter functions are also copied into the target object.

BEFORE…

Before — Using Object.assign

Before — Using Object.assign

AFTER…

ECMAScript 2017 (ES8) — Object.getOwnPropertyDescriptors

ECMAScript 2017 (ES8) — Object.getOwnPropertyDescriptors

var Car = {

name: 'BMW',

price: 1000000,

set discount(x) {

this.d = x;

},

get discount() {

return this.d;

},

};

//Print details of Car object's 'discount' property

console.log(Object.getOwnPropertyDescriptor(Car, 'discount'));

//prints..

// {

// get: [Function: get],

// set: [Function: set],

// enumerable: true,

// configurable: true

// }

//Copy Car's properties to ElectricCar using Object.assign

const ElectricCar = Object.assign({}, Car);

//Print details of ElectricCar object's 'discount' property

console.log(Object.getOwnPropertyDescriptor(ElectricCar, 'discount'));

//prints..

// {

// value: undefined,

// writable: true,

// enumerable: true,

// configurable: true

// }

//⚠️Notice that getters and setters are missing in ElectricCar object for 'discount' property !👎👎

//Copy Car's properties to ElectricCar2 using Object.defineProperties

//and extract Car's properties using Object.getOwnPropertyDescriptors

const ElectricCar2 = Object.defineProperties({}, Object.getOwnPropertyDescriptors(Car));

//Print details of ElectricCar2 object's 'discount' property

console.log(Object.getOwnPropertyDescriptor(ElectricCar2, 'discount'));

//prints..

// { get: [Function: get], 👈🏼👈🏼👈🏼

// set: [Function: set], 👈🏼👈🏼👈🏼

// enumerable: true,

// configurable: true

// }

// Notice that getters and setters are present in the ElectricCar2 object for 'discount' property!

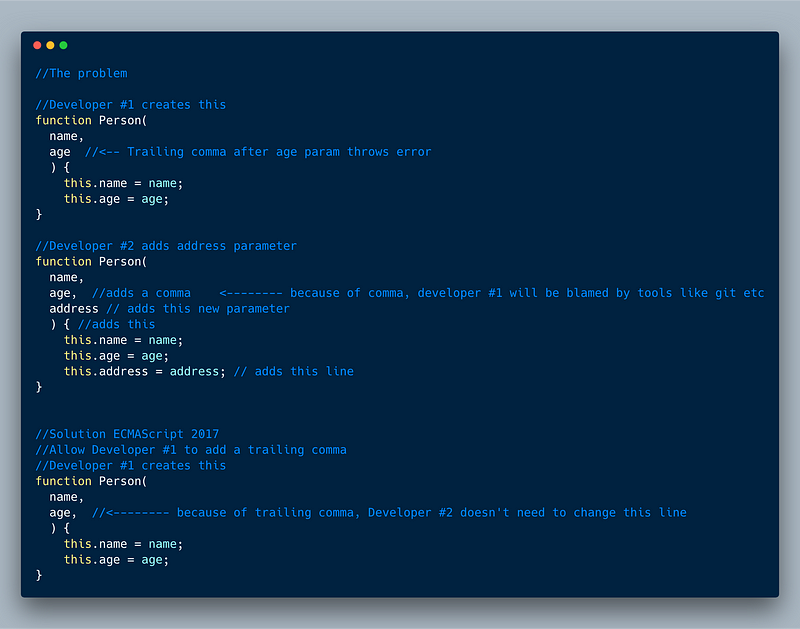

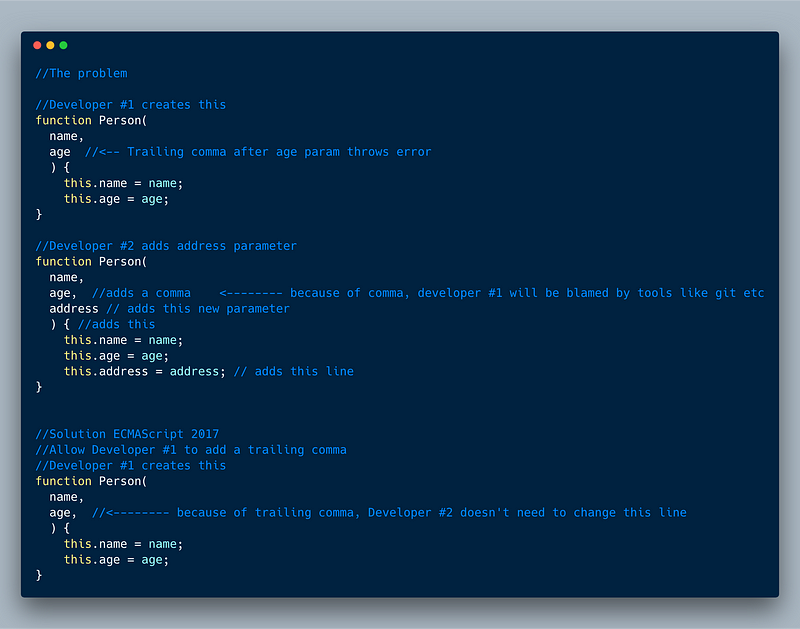

5. Add trailing commas in the function parameters

This is a minor update that allows us to have trailing commas after the last function parameter. Why? To help with tools like git blame to ensure only new developers get blamed.

The below example shows the problem and the solution.

ECMAScript 2017 (ES 8) — Trailing comma in function paramameter

ECMAScript 2017 (ES 8) — Trailing comma in function paramameter

Note: You can also call functions with trailing commas!

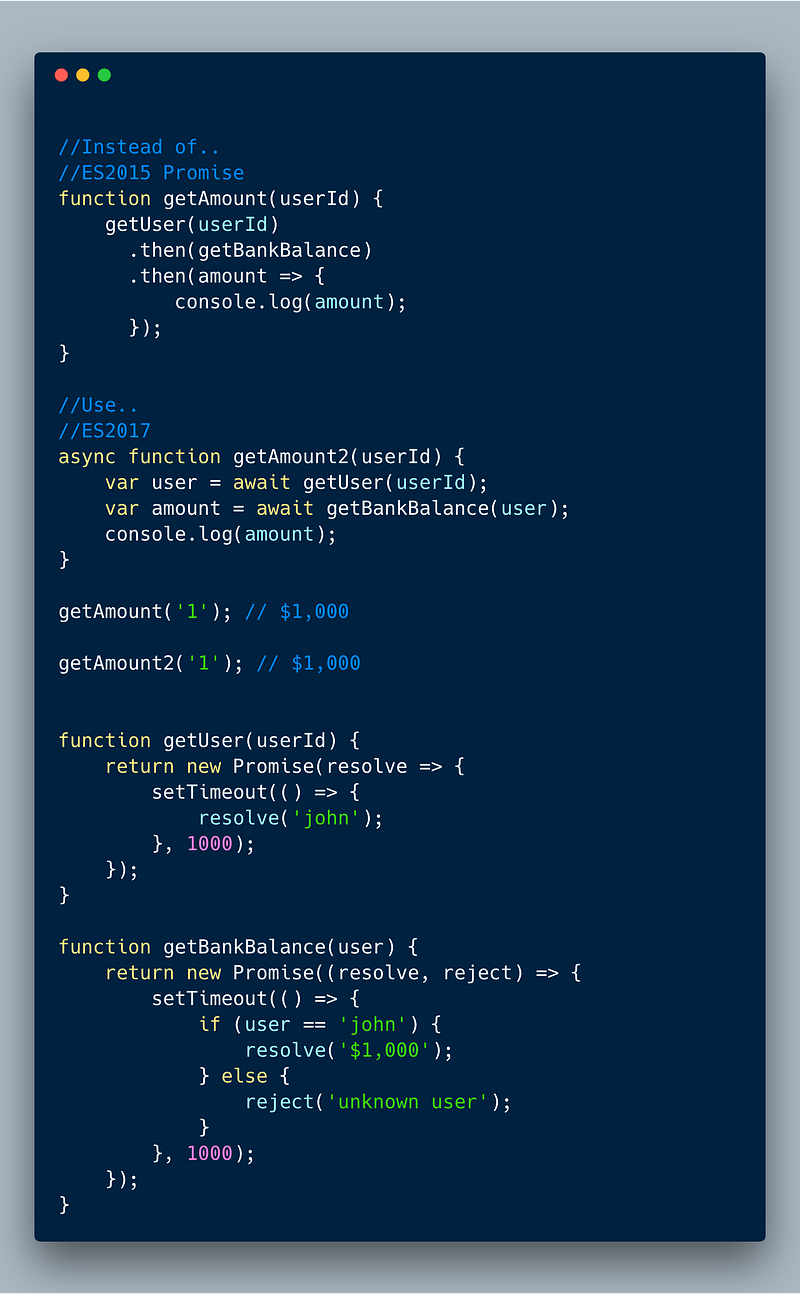

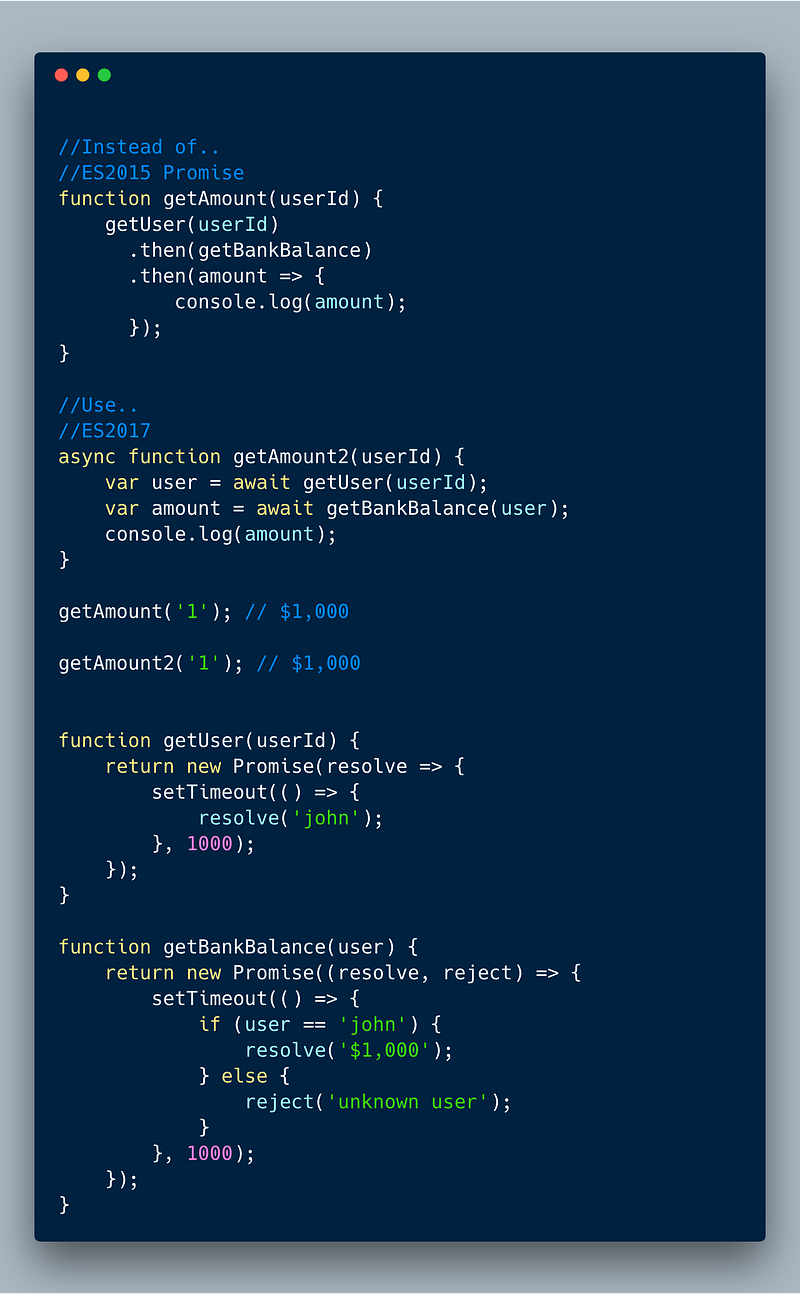

6. Async/Await

This, by far, is the most important and most useful feature if you ask me. Async functions allows us to not deal with callback hell and make the entire code look simple.

The async keyword tells the JavaScript compiler to treat the function differently. The compiler pauses whenever it reaches the await keyword within that function. It assumes that the expression after await returns a promise and waits until the promise is resolved or rejected before moving further.

In the example below, the getAmount function is calling two asynchronous functions getUser and getBankBalance . We can do this in promise, but using async await is more elegant and simple.

ECMAScript 2017 (ES 8) — Async Await basic example

ECMAScript 2017 (ES 8) — Async Await basic example

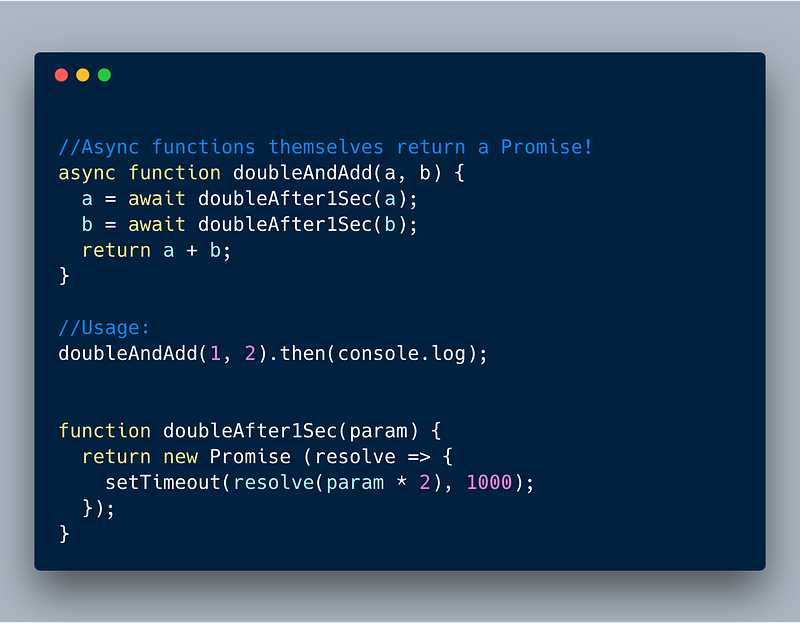

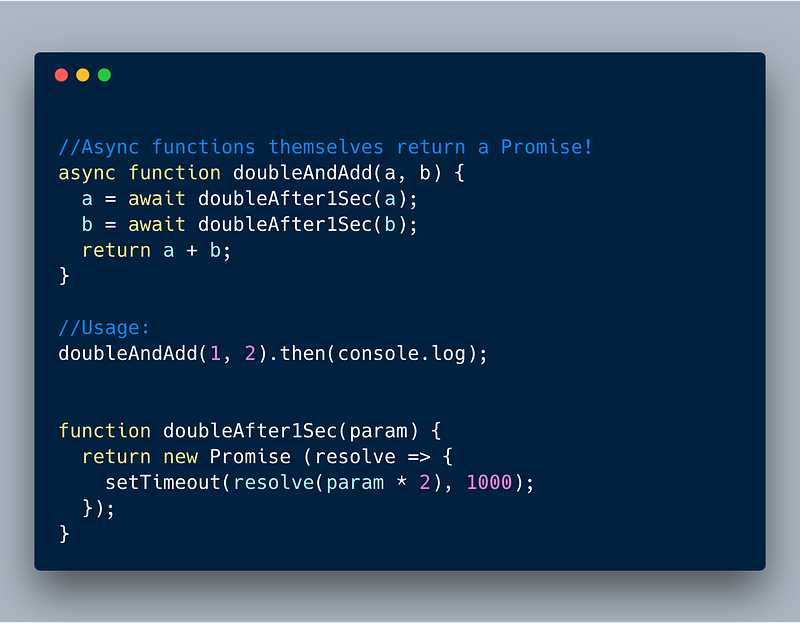

6.1 Async functions themselves return a Promise.

If you are waiting for the result from an async function, you need to use Promise’s then syntax to capture its result.

In the following example, we want to log the result using console.log but not within the doubleAndAdd. So we want to wait and use then syntax to pass the result to console.log .

ECMAScript 2017 (ES 8) — Async Await themselves returns Promise

ECMAScript 2017 (ES 8) — Async Await themselves returns Promise

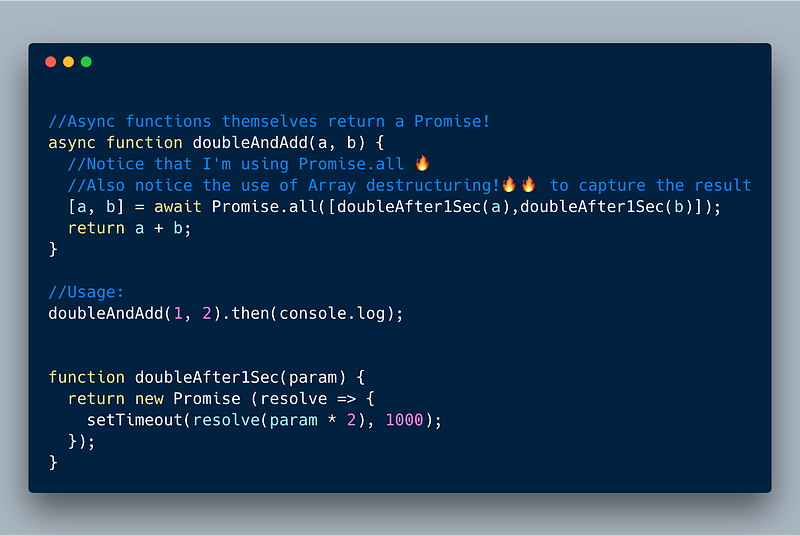

6.2 Calling async/await in parallel

In the previous example we are calling await twice, but each time we are waiting for one second (total 2 seconds). Instead we can parallelize it since a and b are not dependent on each other using Promise.all.

ECMAScript 2017 (ES 8) — Using Promise.all to parallelize async/await

ECMAScript 2017 (ES 8) — Using Promise.all to parallelize async/await

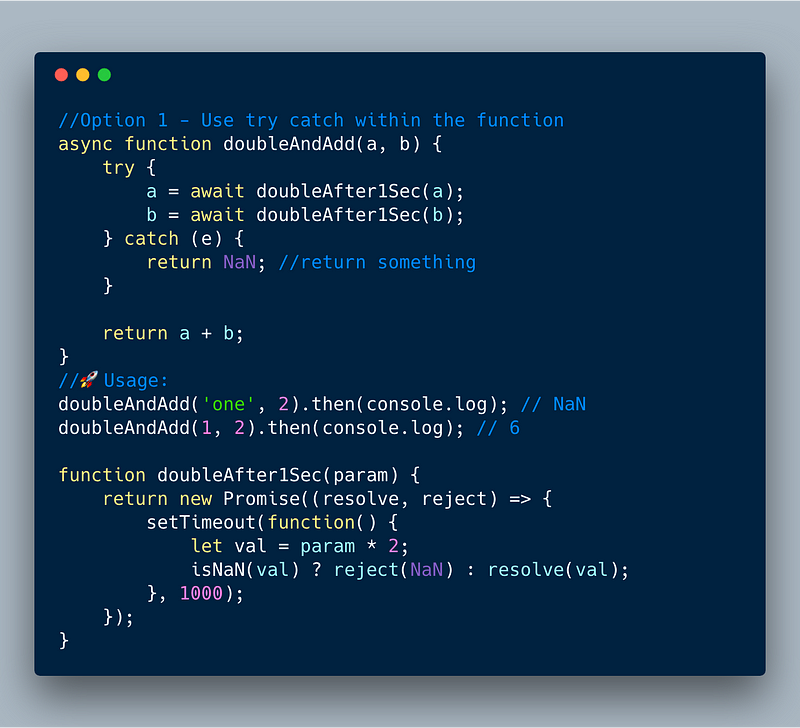

6.3 Error handling async/await functions

There are various ways to handle errors when using async await.

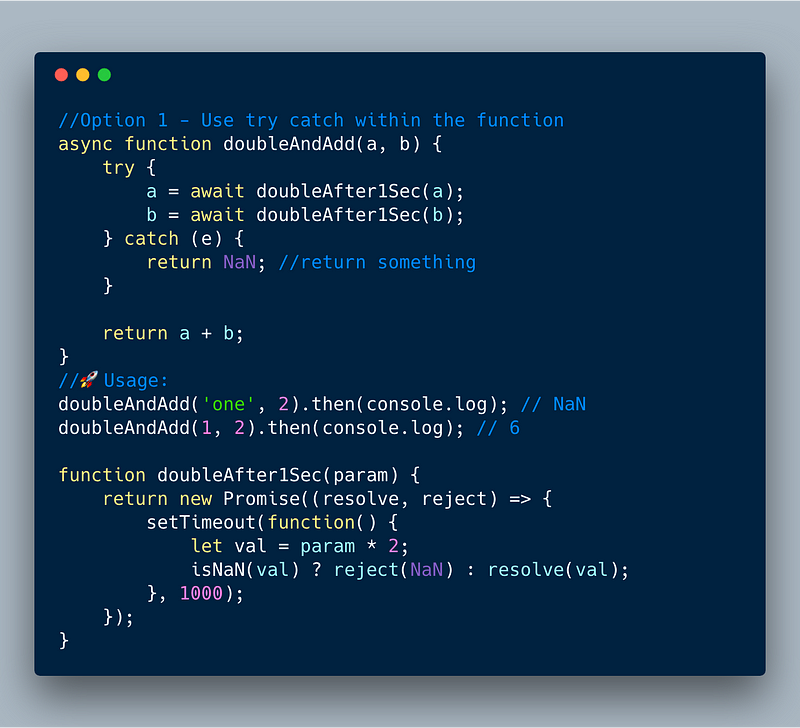

Option 1 — Use try catch within the function

ECMAScript 2017 — Use try catch within the async/await function

ECMAScript 2017 — Use try catch within the async/await function

//Option 1 - Use try catch within the function

async function doubleAndAdd(a, b) {

try {

a = await doubleAfter1Sec(a);

b = await doubleAfter1Sec(b);

} catch (e) {

return NaN; //return something

}

return a + b;

}

//🚀Usage:

doubleAndAdd('one', 2).then(console.log); // NaN

doubleAndAdd(1, 2).then(console.log); // 6

function doubleAfter1Sec(param) {

return new Promise((resolve, reject) => {

setTimeout(function() {

let val = param * 2;

isNaN(val) ? reject(NaN) : resolve(val);

}, 1000);

});

}

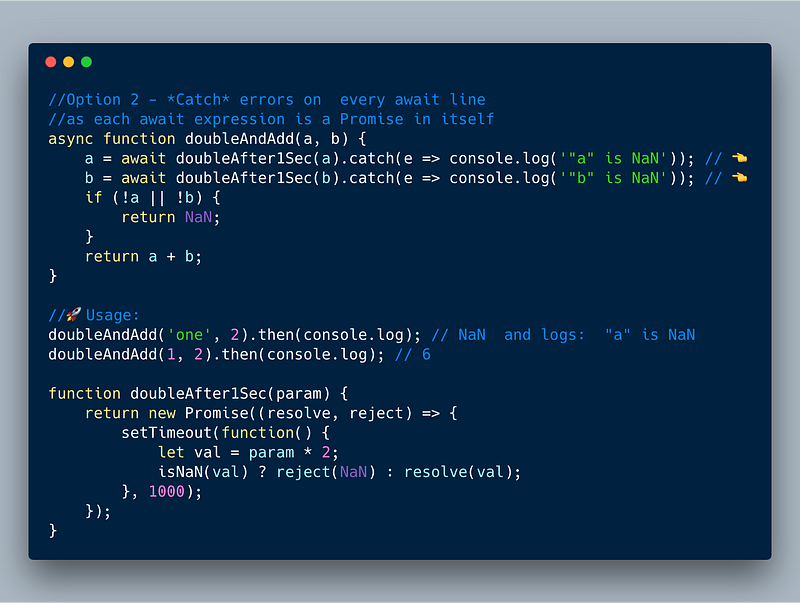

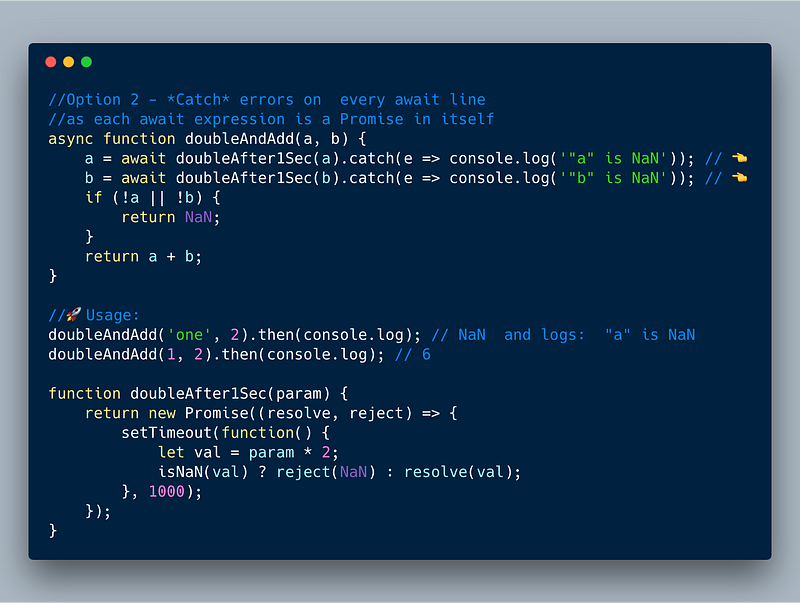

Option 2— Catch every await expression

Since every await expression returns a Promise, you can catch errors on each line as shown below.

ECMAScript 2017 — Use try catch every await expression

ECMAScript 2017 — Use try catch every await expression

//Option 2 - *Catch* errors on every await line

//as each await expression is a Promise in itself

async function doubleAndAdd(a, b) {

a = await doubleAfter1Sec(a).catch(e => console.log('"a" is NaN')); // 👈

b = await doubleAfter1Sec(b).catch(e => console.log('"b" is NaN')); // 👈

if (!a || !b) {

return NaN;

}

return a + b;

}

//🚀Usage:

doubleAndAdd('one', 2).then(console.log); // NaN and logs: "a" is NaN

doubleAndAdd(1, 2).then(console.log); // 6

function doubleAfter1Sec(param) {

return new Promise((resolve, reject) => {

setTimeout(function() {

let val = param * 2;

isNaN(val) ? reject(NaN) : resolve(val);

}, 1000);

});

}

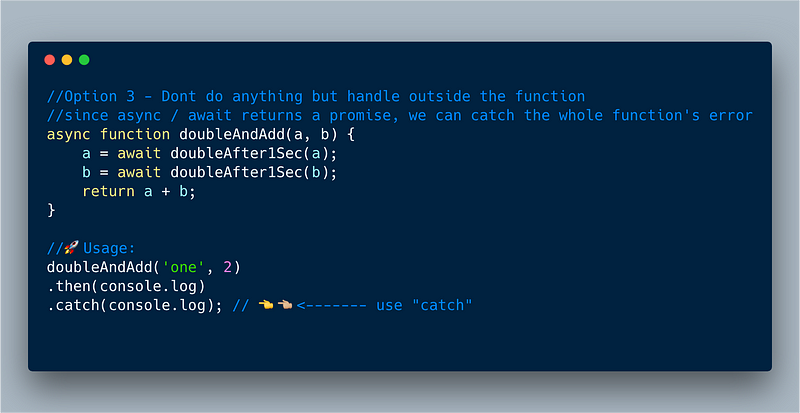

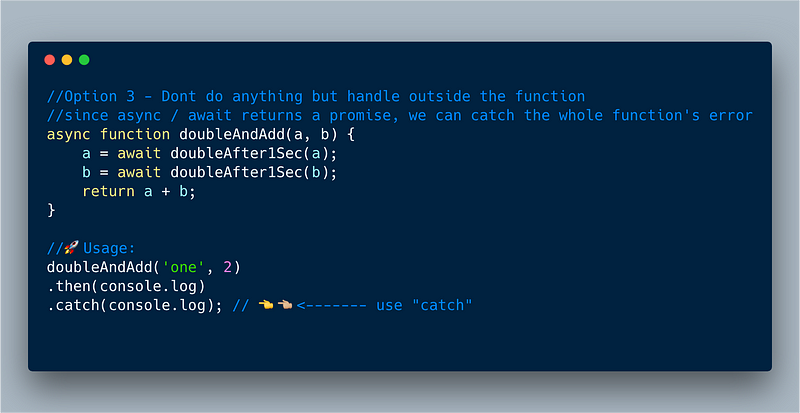

Option 3 — Catch the entire async-await function

ECMAScript 2017 — Catch the entire async/await function at the end

ECMAScript 2017 — Catch the entire async/await function at the end

//Option 3 - Dont do anything but handle outside the function

//since async / await returns a promise, we can catch the whole function's error

async function doubleAndAdd(a, b) {

a = await doubleAfter1Sec(a);

b = await doubleAfter1Sec(b);

return a + b;

}

//🚀Usage:

doubleAndAdd('one', 2)

.then(console.log)

.catch(console.log); // 👈👈🏼<------- use "catch"

function doubleAfter1Sec(param) {

return new Promise((resolve, reject) => {

setTimeout(function() {

let val = param * 2;

isNaN(val) ? reject(NaN) : resolve(val);

}, 1000);

});

}

ECMAScript is currently in final draft and will be out in June or July 2018. All the features covered below are in Stage-4 and will be part of ECMAScript 2018.

1. Shared memory and atomics

This is a huge, pretty advanced feature and is a core enhancement to JS engines.

The main idea is to bring some sort of multi-threading feature to JavaScript so that JS developers can write high-performance, concurrent programs in the future by allowing to manage memory by themselves instead of letting JS engine manage memory.

This is done by a new type of a global object called SharedArrayBuffer that essentially stores data in a _shared_ memory space. So this data can be shared between the main JS thread and web-worker threads.

Until now, if we want to share data between the main JS thread and web-workers, we had to copy the data and send it to the other thread using postMessage . Not anymore!

You simply use SharedArrayBuffer and the data is instantly accessible by both the main thread and multiple web-worker threads.

But sharing memory between threads can cause race conditions. To help avoid race conditions, the “_Atomics_” global object is introduced. Atomics provides various methods to lock the shared memory when a thread is using its data. It also provides methods to update such data in that shared memory safely.

The recommendation is to use this feature via some library, but right now there are no libraries built on top of this feature.

If you are interested, I recommend reading:

- _From Workers to Shared Memor__y — __lucasfcosta_

- _A cartoon intro to SharedArrayBuffers__ — __Lin Clark_

- _Shared memory and atomics__ — __Dr. Axel Rauschmayer_

2. Tagged Template literal restriction removed

First, we need to clarify what a “Tagged Template literal” is so we can understand this feature better.

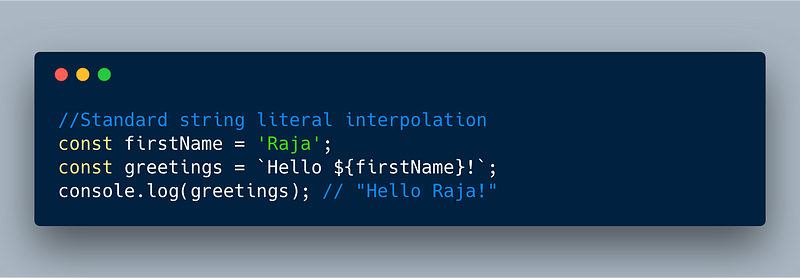

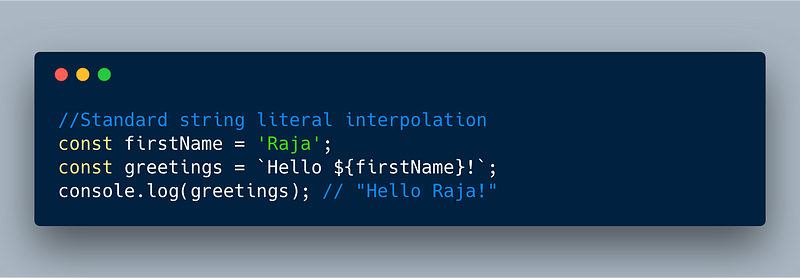

In ES2015+, there is a feature called a tagged template literal that allows developers to customize how strings are interpolated. For example, in the standard way strings are interpolated like below…

In the tagged literal, you can write a function to receive the hardcoded parts of the string literal, for example [ ‘Hello ‘, ‘!’ ] , and the replacement variables, for example,[ 'Raja'] , as parameters into a custom function (for example greet ), and return whatever you want from that custom function.

The below example shows that our custom “Tag” function greet appends time of the day like “Good Morning!” “Good afternoon,” and so on depending on the time of the day to the string literal and returns a custom string.

Tag function example that shows custom string interpolation

Tag function example that shows custom string interpolation

//A "Tag" function returns a custom string literal. //In this example, greet calls timeGreet() to append Good //Morning/Afternoon/Evening depending on the time of the day.

function greet(hardCodedPartsArray, ...replacementPartsArray) {

console.log(hardCodedPartsArray); //[ 'Hello ', '!' ]

console.log(replacementPartsArray); //[ 'Raja' ]

let str = '';

hardCodedPartsArray.forEach((string, i) => {

if (i < replacementPartsArray.length) {

str += `${string} ${replacementPartsArray[i] || ''}`;

} else {

str += `${string} ${timeGreet()}`; //<-- append Good morning/afternoon/evening here

}

});

return str;

}

//🚀Usage:

const firstName = 'Raja';

const greetings = greet`Hello ${firstName}!`; //👈🏼<-- Tagged literal

console.log(greetings); //'Hello Raja! Good Morning!' 🔥

function timeGreet() {

const hr = new Date().getHours();

return hr < 12

? 'Good Morning!'

: hr < 18 ? 'Good Afternoon!' : 'Good Evening!';

}

Now that we discussed what “Tagged” functions are, many people want to use this feature in different domains, like in Terminal for commands and HTTP requests for composing URIs, and so on.

⚠️The problem with Tagged String literal

The problem is that ES2015 and ES2016 specs doesn’t allow using escape characters like “\u” (unicode), “\x”(hexadecimal) unless they look exactly like \u00A9 or \u{2F804} or \xA9.

So if you have a Tagged function that internally uses some other domain’s rules (like Terminal’s rules), that may need to use \ubla123abla that doesn’t look like \u0049 or \u{@F804}, then you would get a syntax error.

In ES2018, the rules are relaxed to allow such seemingly invalid escape characters as long as the Tagged function returns the values in an object with a “cooked” property (where invalid characters are “undefined”), and then a “raw” property (with whatever you want).

function myTagFunc(str) { return { "cooked": "undefined", "raw": str.raw[0] }} var str = myTagFunc `hi \

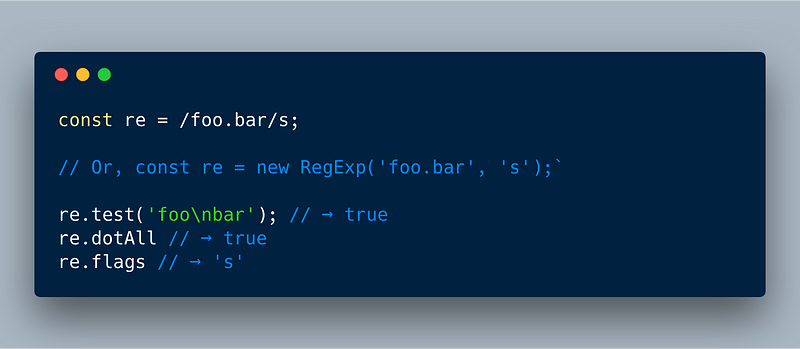

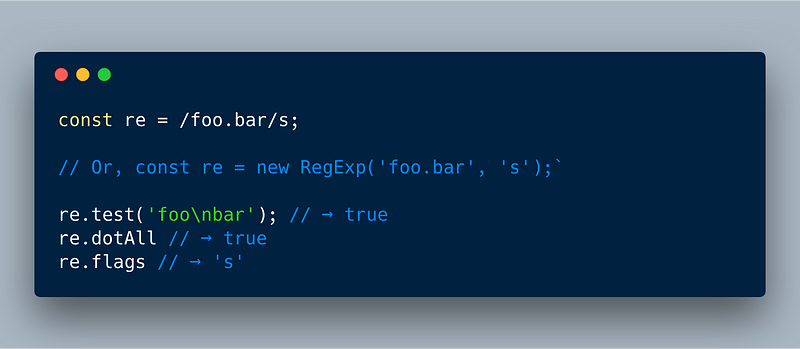

3. “dotall” flag for Regular expression

Currently in RegEx, although the dot(“.”) is supposed to match a single character, it doesn’t match new line characters like \n \r \f etc.

For example:

//Before

/first.second/.test('first\nsecond'); //false

This enhancement makes it possible for the dot operator to match any single character. In order to ensure this doesn’t break anything, we need to use \s flag when we create the RegEx for this to work.

//ECMAScript 2018

/first.second**/s**.test('first\nsecond'); **//true** Notice: /s 👈🏼

Here is the overall API from the proposal doc:

ECMAScript 2018 — Regex dotAll feature allows matching even \n via “.” via /s flag

ECMAScript 2018 — Regex dotAll feature allows matching even \n via “.” via /s flag

4. RegExp Named Group Captures 🔥

This enhancement brings a useful RegExp feature from other languages like Python, Java and so on called “Named Groups.” This features allows developers writing RegExp to provide names (identifiers) in the format(?<name>...) for different parts of the group in the RegExp. They can then use that name to grab whichever group they need with ease.

4.1 Basic Named group example

In the below example, we are using (?<year>) (?<month>) and (?<day>) names to group different parts of the date RegEx. The resulting object will now contain a groups property with properties year, month , and day with corresponding values.

ECMAScript 2018 — Regex named groups example

ECMAScript 2018 — Regex named groups example

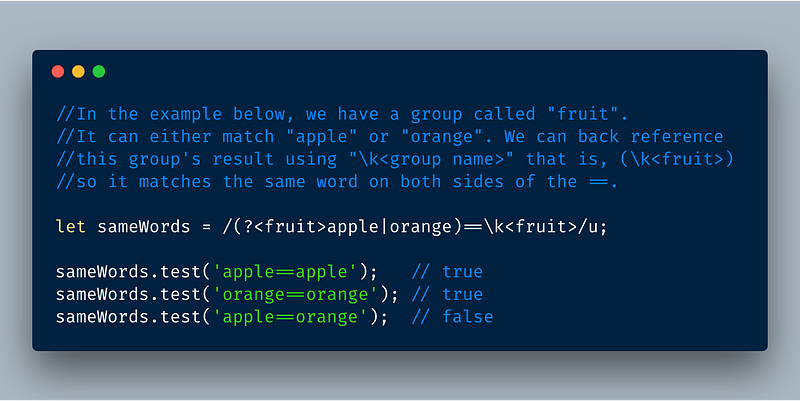

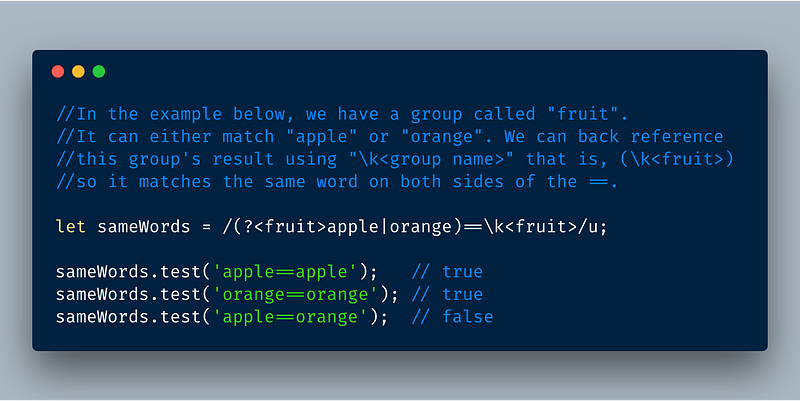

4.2 Using Named groups inside regex itself

We can use the \k<group name> format to back reference the group within the regex itself. The following example shows how it works.

ECMAScript 2018 — Regex named groups back referencing via \k

ECMAScript 2018 — Regex named groups back referencing via \k

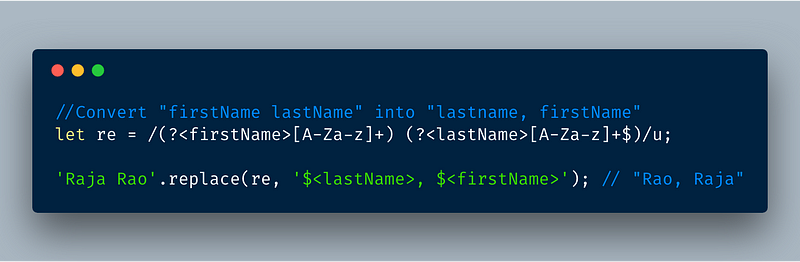

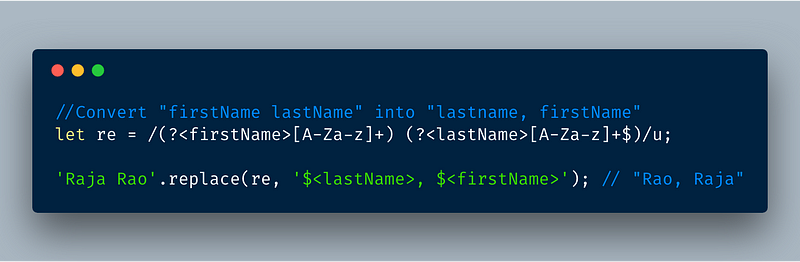

4.3 Using named groups in String.prototype.replace

The named group feature is now baked into String’s replace instance method. So we can easily swap words in the string.

For example, change “firstName, lastName” to “lastName, firstName”.

ECMAScript 2018 — Using RegEx’s named groups feature in replace function

ECMAScript 2018 — Using RegEx’s named groups feature in replace function

5. Rest properties for Objects

Rest operator ... (three dots) allows us to extract Object properties that are not already extracted.

5.1 You can use rest to help extract only properties you want

ECMAScript 2018 — Object destructuring via rest

ECMAScript 2018 — Object destructuring via rest

5.2 Even better, you can remove unwanted items! 🔥🔥

ECMAScript 2018 — Object destructuring via rest

ECMAScript 2018 — Object destructuring via rest

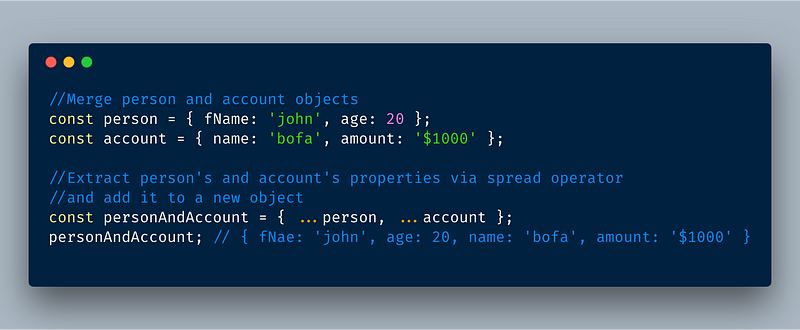

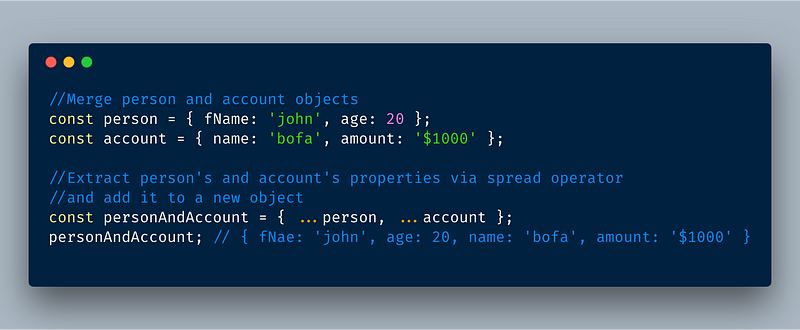

6. Spread properties for Objects

Spread properties also look just like rest properties with three dots ... but the difference is that you use spread to create (restructure) new objects.

Tip: the spread operator is used in the right side of the equals sign. The rest are used in the left-side of the equals sign.

ECMAScript 2018 — Object restructuring via spread

ECMAScript 2018 — Object restructuring via spread

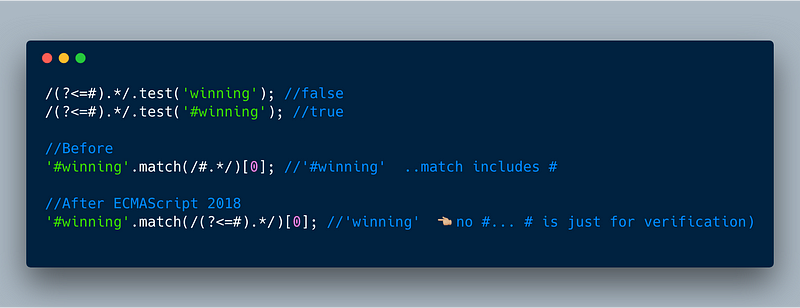

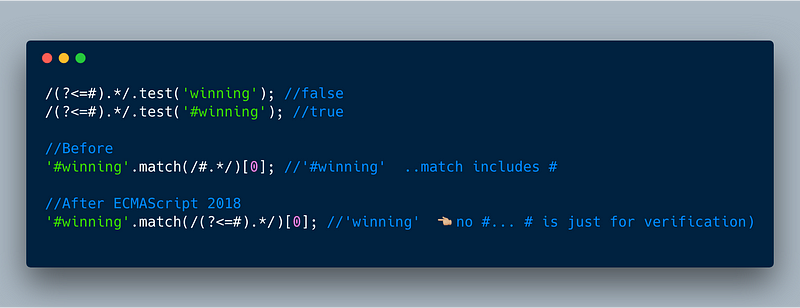

7. RegExp Lookbehind Assertions

This is an enhancement to the RegEx that allows us to ensure some string exists immediately _before_ some other string.

You can now use a group (?<=…) (question mark, less than, equals) to look behind for positive assertion.

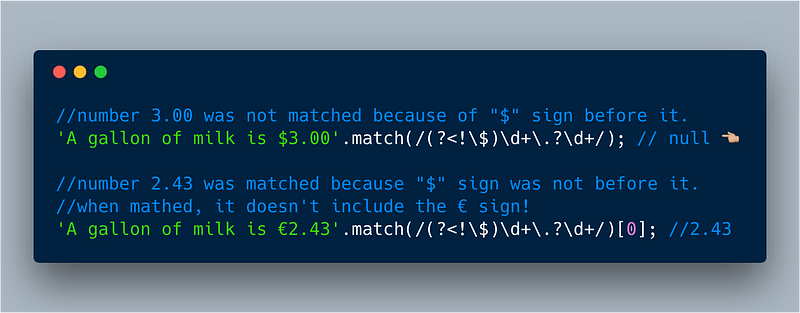

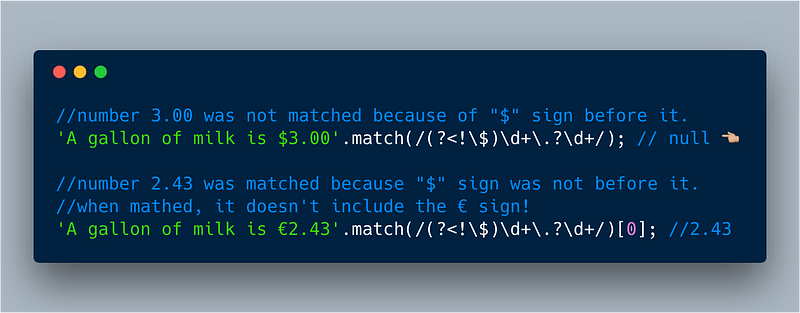

Further, you can use (?<!…) (question mark, less than, exclamation), to look behind for a negative assertion. Essentially this will match as long as the -ve assertion passes.

Positive Assertion: Let’s say we want to ensure that the # sign exists before the word winning (that is: #winning) and want the regex to return just the string “winning”. Here is how you’d write it.

ECMAScript 2018 —

ECMAScript 2018 — (?<=…) for positive assertion

Negative Assertion: Let’s say we want to extract numbers from lines that have € signs and not $ signs before those numbers.

ECMAScript 2018 — (?<!…) for negative assertions

ECMAScript 2018 — (?<!…) for negative assertions

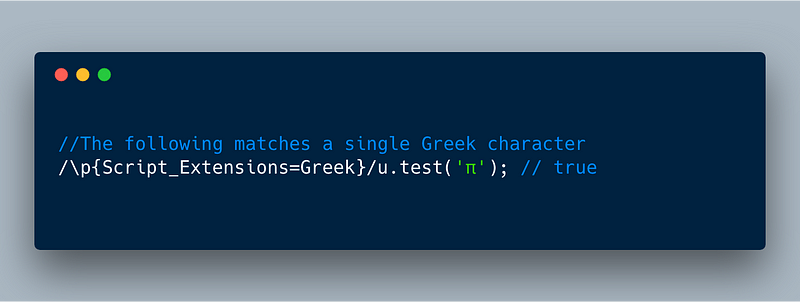

8. RegExp Unicode Property Escapes

It was not easy to write RegEx to match various unicode characters. Things like \w , \W , \d etc only match English characters and numbers. But what about numbers in other languages like Hindi, Greek, and so on?

That’s where Unicode Property Escapes come in. It turns out Unicode adds metadata properties for each symbol (character) and uses it to group or characterize various symbols.

For example, Unicode database groups all Hindi characters(हिन्दी) under a property called Script with value Devanagari and another property called Script_Extensions with the same value Devanagari. So we can search for Script=Devanagari and get all Hindi characters.

Devanagari can be used for various Indian languages like Marathi, Hindi, Sanskrit, and so on.

Starting in ECMAScript 2018, we can use \p to escape characters along with {Script=Devanagari} to match all those Indian characters. That is, we can use: **\p{Script=Devanagari}** in the RegEx to match all Devanagari characters.

ECMAScript 2018 — showing \p

ECMAScript 2018 — showing \p

//The following matches multiple hindi character

**/^\p{Script=Devanagari}+$/u.test('हिन्दी'); //true **

//PS:there are 3 hindi characters h

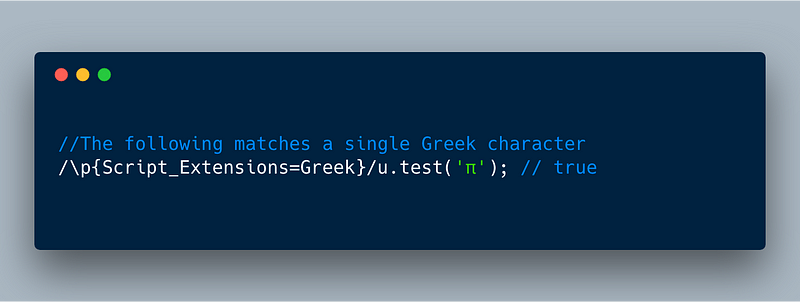

Similarly, Unicode database groups all Greek characters under Script_Extensions (and Script ) property with the value Greek . So we can search for all Greek characters using Script_Extensions=Greek or Script=Greek .

That is, we can use: **\p{Script=Greek}** in the RegEx to match all Greek characters.

ECMAScript 2018 — showing \p

ECMAScript 2018 — showing \p

//The following matches a single Greek character

**/\p{Script_Extensions=Greek}/u.test('π');** // true

Further, the Unicode database stores various types of Emojis under the boolean properties Emoji, Emoji_Component, Emoji_Presentation, Emoji_Modifier, and Emoji_Modifier_Base with property values as true. So we can search for all Emojis by simply selecting Emoji to be true.

That is, we can use: **\p{Emoji}** ,**\Emoji_Modifier** and so on to match various kinds of Emojis.

The following example will make it all clear.

ECMAScript 2018 — showing how \p can be used for various emojis

ECMAScript 2018 — showing how \p can be used for various emojis

//The following matches an Emoji character

/\p{Emoji}/u.test('❤️'); //true

//The following fails because yellow emojis don't need/have Emoji_Modifier!

/\p{Emoji}\p{Emoji_Modifier}/u.test('✌️'); //false

//The following matches an emoji character\p{Emoji} followed by \p{Emoji_Modifier}

/\p{Emoji}\p{Emoji_Modifier}/u.test('✌🏽'); //true

//Explaination:

//By default the victory emoji is yellow color.

//If we use a brown, black or other variations of the same emoji, they are considered

//as variations of the original Emoji and are represented using two unicode characters.

//One for the original emoji, followed by another unicode character for the color.

//

//So in the below example, although we only see a single brown victory emoji,

//it actually uses two unicode characters, one for the emoji and another

// for the brown color.

//

//In Unicode database, these colors have Emoji_Modifier property.

//So we need to use both \p{Emoji} and \p{Emoji_Modifier} to properly and

//completely match the brown emoji.

/\p{Emoji}\p{Emoji_Modifier}/u.test('✌🏽'); //true

Lastly, we can use capital "P”(\P ) escape character instead of small p (\p ), to negate the matches.

References:

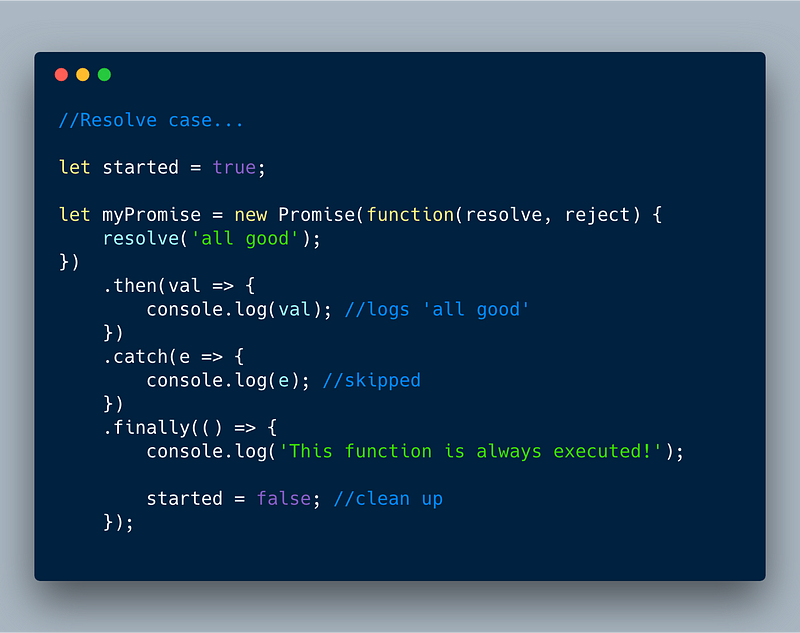

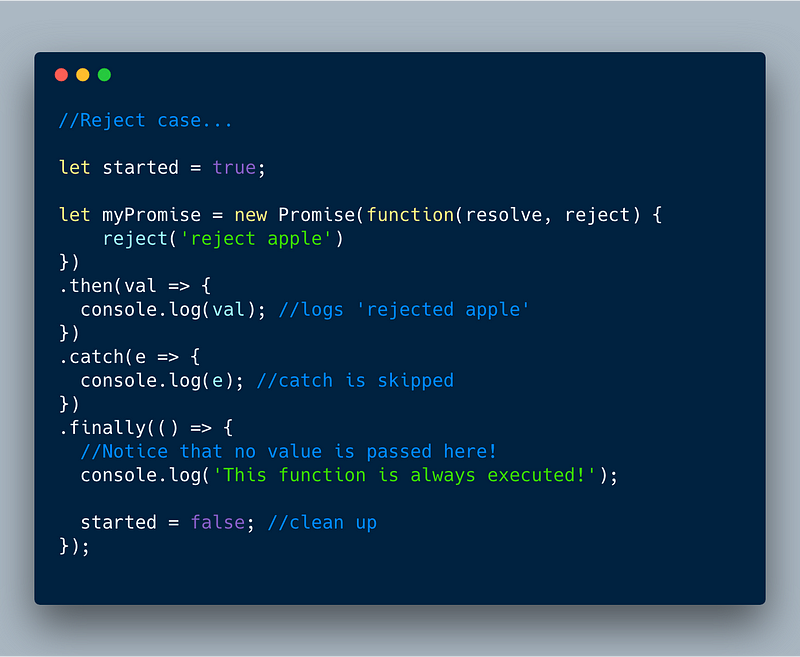

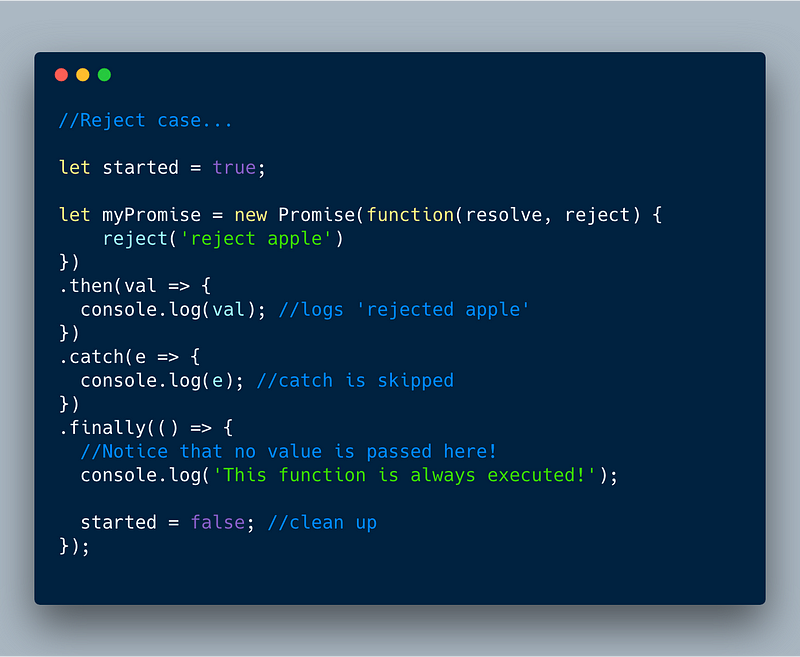

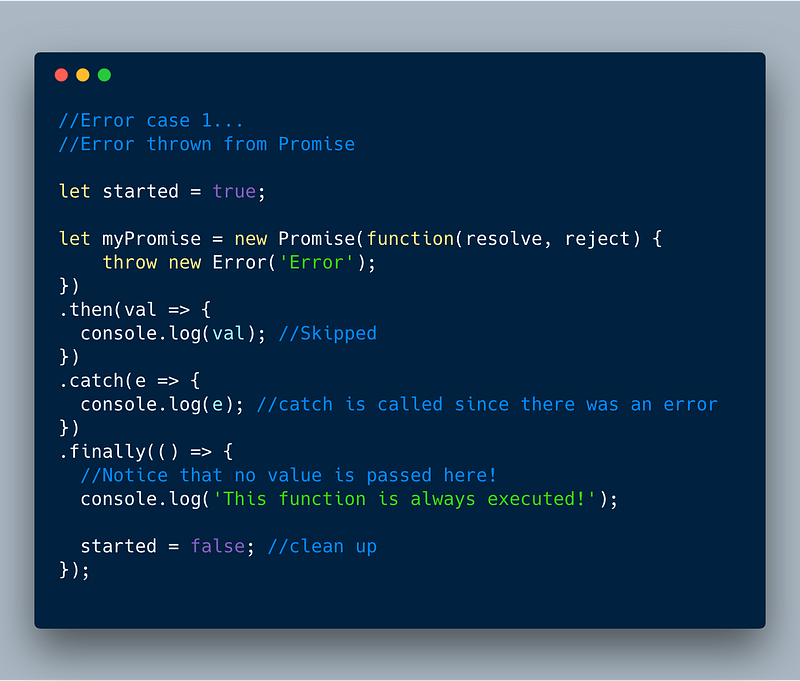

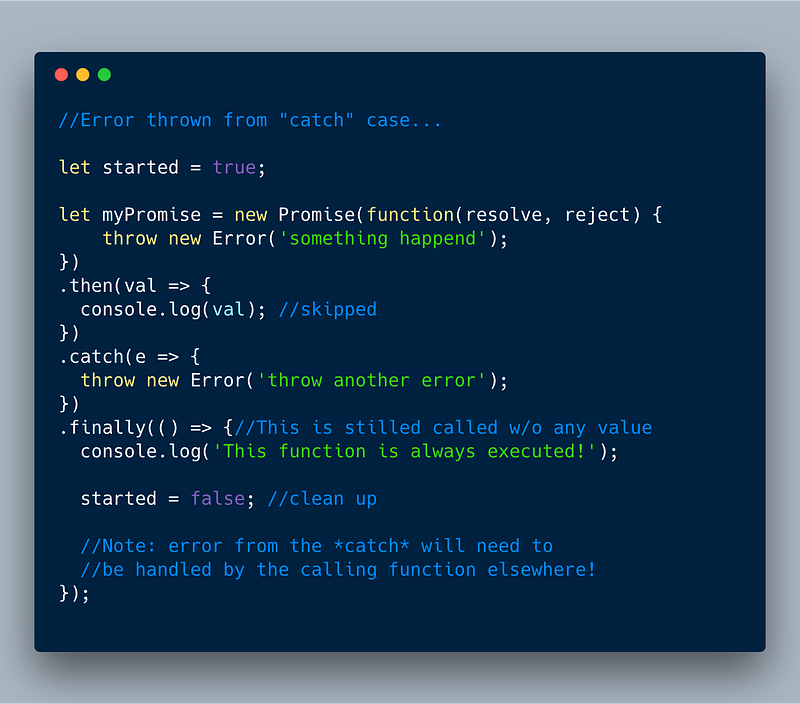

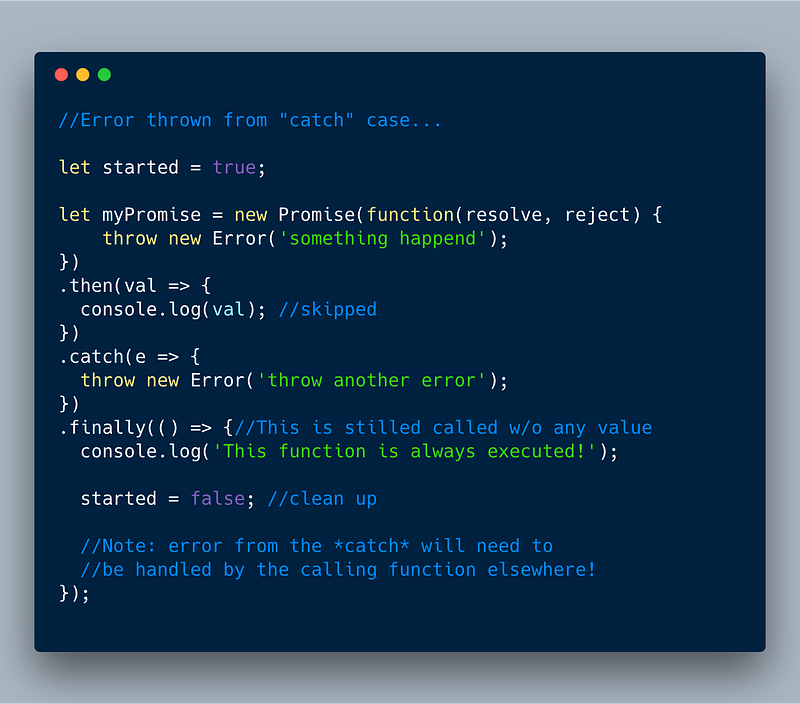

8. Promise.prototype.finally()

finally() is a new instance method that was added to Promise. The main idea is to allow running a callback after either resolve or reject to help clean things up. The **finally** callback is called without any value and is always executed no matter what.

Let’s look at various cases.

ECMAScript 2018 — finally() in resolve case

ECMAScript 2018 — finally() in resolve case

ECMAScript 2018 — finally() in reject case

ECMAScript 2018 — finally() in reject case

ECMASCript 2018 — finally() in Error thrown from Promise case

ECMASCript 2018 — finally() in Error thrown from Promise case

**ECMAScript 2018 — Error thrown from within catch case**

**ECMAScript 2018 — Error thrown from within catch case**

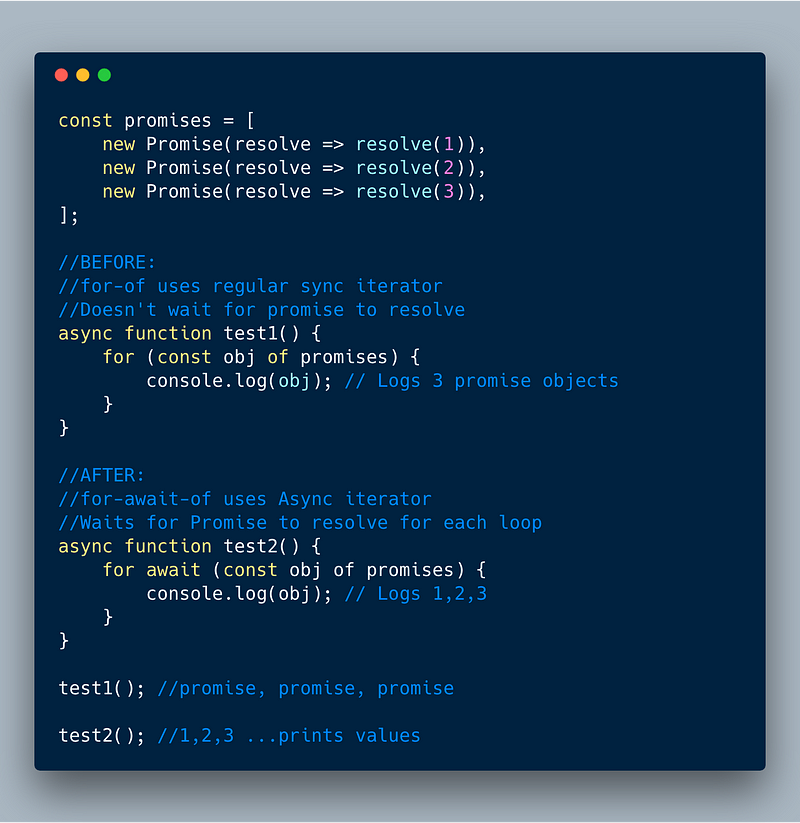

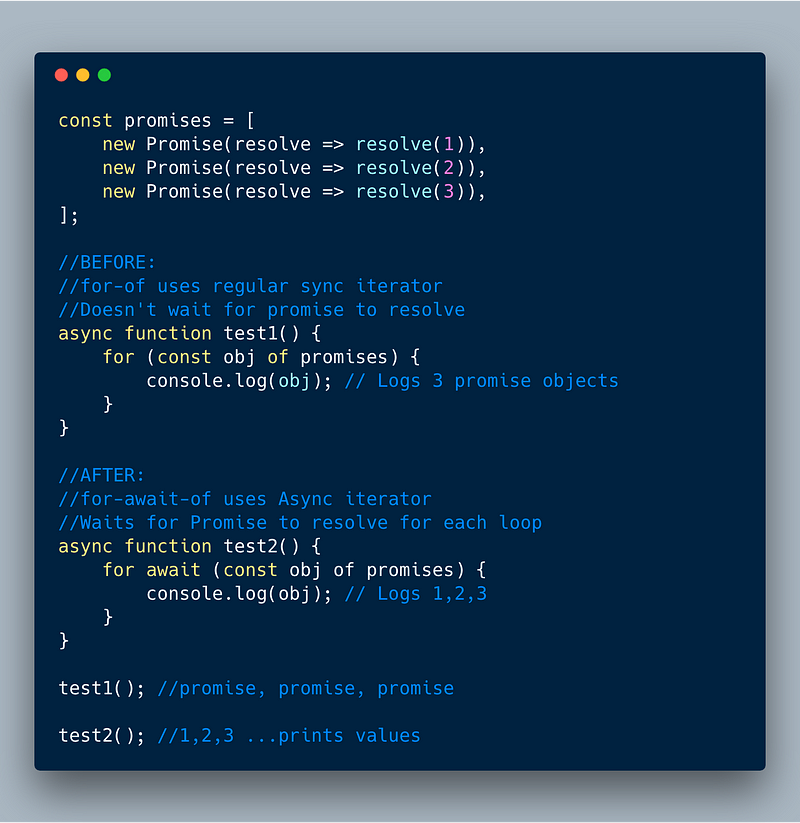

9. Asynchronous Iteration

This is an extremely useful feature. Basically it allows us to create loops of async code with ease!

This feature adds a new “for-await-of” loop that allows us to call async functions that return promises (or Arrays with a bunch of promises) in a loop. The cool thing is that the loop waits for each Promise to resolve before doing to the next loop.

ECMAScript 2018 — Async Iterator via for-await-of

ECMAScript 2018 — Async Iterator via for-await-of

That’s pretty much it!

If this was useful, please click the clap 👏 button down below a few times to show your support! ⬇⬇⬇ 🙏🏼

My Other Posts

_https://medium.com/@rajaraodv/latest_

Related ECMAScript 2015+ posts

Copyright © 2015 Powered by MWeb, Theme used GitHub CSS.